Sample of SOAP Notes Nursing: Best Practices and Examples

Sample of SOAP Notes Nursing #1

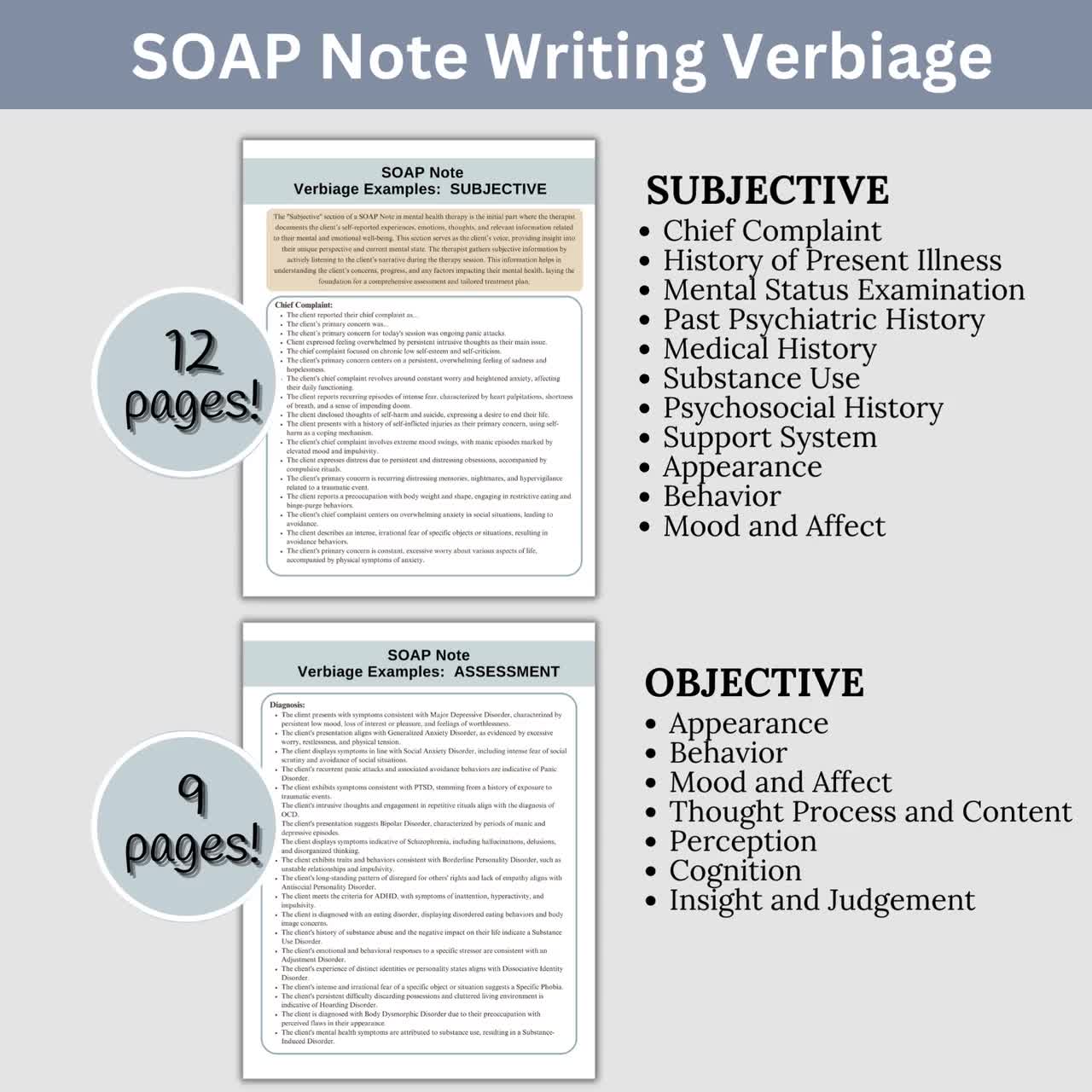

Subjective, Objective, Assessment, Plan (SOAP) Notes

Name: A.N. Other. |

Date: 0/00/00 |

Time:00.00 |

America |

Age: 00 |

Sex: MF |

SUBJECTIVE |

||

Chief Complaint:“I have rashes all over my body.” |

||

History of Present Illness:Onset:The rash began a week ago, according to the patient, and it first appeared on his arms and legs. Location:The rash is spread across his body, including the trunk, limbs, and face, indicating a widespread presentation. Duration:Mr. KG adds that the rash has been persistent and has not improved since it first appeared. Character:The patient describes the rash as red, elevated, and very irritating, emphasizing the discomfort and influence on his sleep caused by itching. Aggravating Factors:The patient has not identified any unique triggers for the rash. He denies using new skincare products, being exposed to new allergies, or experiencing recent environmental changes. Relieving Factors:The major symptom is itching, and Mr. KG denies any related pain. He has seen no blistering, discharge, or scaling. Timing:The patient states that the discomfort is most severe at night, disrupting his sleep. |

||

Medications:The patient is not taking any medication. |

||

Previous Medical HistoryAllergies:There are no known allergies. Medication Intolerances:There have been no reports. Chronic Illnesses/Major traumasThe patient has a history of minor eczema as a child but no serious medical conditions or traumas. Hospitalizations/SurgeriesThere have been no recent hospitalizations or surgeries mentioned. There is no history of chronic medical diseases such as Diabetes, tuberculosis, asthma, heart issues, HTN, PUD, Cancer, tuberculosis, thyroid difficulties, or renal disease. |

||

Family HistoryMr. KG states that neither his parents nor his siblings have any severe medical or psychiatric disorders. There was no family history of dermatological disorders reported.

|

||

Social HistoryThe patient finished high school and is now working as an office administrator. He is married and has two children with his wife. He denies any substance misuse and admits to drinking alcohol on occasion (social drinking). There was no mention of tobacco or marijuana use. The patient’s living environment has been determined to be safe.

|

||

| ETOH, tobacco, marijuana. Safety status | |

Review Of Systems |

|

General

There was no substantial weight change. Itching causes sleep disruption, which causes weariness. Denies the presence of fever, chills, or nocturnal sweats. |

CardiovascularThe patient denies having chest pain or palpitations, and there is no swelling or edema.

|

SkinThe rash is described as red, elevated, and itchy. There are no blisters, discharge, or scaling reported. Denies any recent changes in moles or lesions. There was no history of trauma or skin injury documented. .

|

RespiratoryDenies having a cough, wheezing, or being short of breath. There is no history of coughing up blood. There has been no history of pneumonia or TB.

|

EyesThe patient denies any eyesight blurring or alterations. The patient uses distance vision glasses.

|

GastrointestinalAbdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, or constipation are all denied. There has been no history of hepatitis, hemorrhoids, or ulcers. Denies having ever had an eating disorder.

|

EarsEar pain, hearing loss, tinnitus, or ear discharge are all denied. |

Genitourinary/GynecologicalThere was no mention of urinary urgency, frequency, or burning. Denies any changes in urine color. There has been no history of sexually transmitted infections.

|

Nose/Mouth/Throat

Denies sinus troubles, swallowing difficulties, nosebleeds, dental issues, hoarseness, or throat pain.

|

Musculoskeletal

Denies any history of back problems, joint swelling or pain, fractures, or osteoporosis.

|

Breast

N/A

|

Neurological

Syncope, seizures, brief paralysis, weakness, paresthesias, or blackouts are all denied by the patient.

|

Heme/Lymph/EndoHIV, blood transfusions, nocturnal sweats, swollen glands, excessive thirst, increased hunger, or temperature intolerance are all denied. |

PsychiatricDenies having depression, anxiety, sleeping problems, or suicidal thoughts or attempts. There has been no history of psychiatric diagnoses.

|

OBJECTIVE |

|

| Weight: 000 lbs BMI 23 | Temp 00°F | BP 133/74 mmHg |

| Height 5’9″ | Pulse 73 beats per minute

|

Resp 17 breaths per minute

|

General AppearanceA.N. Other. is a well-dressed, healthy-looking adult male who appears to be at ease and not in immediate danger. He maintains eye contact throughout the interview and speaks clearly.

|

||

Skin

The skin examination reveals many erythematous papules and plaques spread over the body, consistent with a generalized rash. Lesions are somewhat elevated, with some displaying a central clearing. There are no vesicles or pustules identified. There are no symptoms of trauma or secondary illness.

|

||

Head, eyes, ears, nose, and throat (HEENT)Normalocephalic, atraumatic head. Pupils are equal, round, reactive to light, and accommodating (PERRLA), and there is no conjunctival injection or discharge. Canals are patent, TMs are intact, and there is no discharge. Nose: Pink nasal mucosa, no septal deviation. Throat: Clear oropharynx with no erythema or exudate.

|

||

Cardiovascular

S1 and S2 heart sounds are present, with a steady beat and no murmurs, rubs, or gallops. Capillary refill is within normal limits, with pulses 2+ throughout.

|

||

RespiratoryAuscultation of the lungs revealed no wheezing or crackles.

|

||

GastrointestinalThe abdomen is soft and non-tender, with bowel sounds in all quadrants and no hepatosplenomegaly. There are no signs of peritonitis. |

||

BreastN/A |

||

Genitourinary

External genitalia were normal, with no lesions. |

||

Musculoskeletal

All extremities had a full range of motion and no joint swelling or deformity.

|

||

NeurologicalThe patient is alert and oriented. Speech is clear. No focal deficits were noted. Gait normal. |

||

PsychiatricThe patient is aware and focused, with fluent speech and no focal impairments. His gait is normal. Laboratory Examinations |

||

Lab TestsCBC |

Special Tests |

Diagnosis |

Differential DiagnosesScabies: (ICD-10 Code: B86 (Scabies))Scabies is caused by an infestation of the skin by the Sarcoptes scabies mite, which burrows into the epidermis and lays eggs, triggering an immune response characterized by itching, inflammation, and the development of papules, vesicles, and burrows. The intense itching, particularly at night, is caused by both the immune response and the mite’s physical presence. Nummular Eczema (ICD-10 Code: L30.0 (Nummular dermatitis))Nummular, or discoid eczema, is a chronic inflammatory skin disorder. While the exact cause is unknown, it is often associated with dry skin and a compromised skin barrier. Disruptions in the skin barrier allow irritants to penetrate, triggering an immune response that manifests as coin-shaped plaques with a distinctive appearance. Pityriasis Rosea (ICD-10 Code: L42 (Pityriasis rosea))Pityriasis rosea is a self-limiting skin condition with a viral etiology, possibly linked to human herpesvirus 6 or 7. The exact pathophysiology is unknown, but it typically begins with a single, larger herald patch, followed by the appearance of smaller lesions in a distinctive distribution on the trunk and extremities. The rash is a manifestation of an immune response to the viral infection. Diagnosis1. Allergic Contact Dermatitis (ICD-10 Code: L23.9 (Allergic contact dermatitis, unspecified cause))Allergic contact dermatitis is an inflammatory skin condition caused by allergen exposure. The process begins with sensitization, in which the immune system identifies a substance as harmful. Upon subsequent exposure, the allergen triggers a delayed hypersensitivity reaction. T lymphocytes are activated, releasing inflammatory mediators such as histamines, which cause vasodilation, erythema, and increased vascular permeability, resulting in pruritus. |

Plan/Therapeutics |

o Plan:Further testingPatch Testing:Patch testing is critical for identifying specific allergens responsible for ACD (Garg et al., 2021). It involves applying small amounts of potential allergens to the patient’s skin under occlusion. The patches remain in place for 48 to 72 hours, mimicking exposure conditions. Depending on the patient’s history, dermatologists will apply a standard set of allergens and additional substances. Reactions are assessed after patch removal. Photopatch Testing:When allergen exposure occurs in conjunction with sunlight, photopatch testing may be warranted to identify photoallergic reactions (Tanahashi et al., 2019). Photopatch testing is similar to patch testing but with an additional exposure to ultraviolet (UV) light on specific patches to mimic sunlight exposure. Irritant Patch Testing:Differentiating between allergic and irritant reactions is critical, and irritant patch testing can assist in identifying compounds causing non-allergic irritation (Foti et al., 2021). Laboratory Tests:To rule out underlying conditions or assess overall health, laboratory tests such as blood tests may sometimes be recommended (Goolsby & Grubbs, 2018). Blood tests may include a complete blood count (CBC) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) to evaluate for systemic involvement. MedicationTopical Corticosteroid (Clobetasol Propionate 0.05% Cream):Clobetasol propionate is a potent corticosteroid that helps reduce inflammation, itching, and redness associated with ACD (Vanderah, 2023). The tapering approach minimizes the risk of side effects associated with long-term corticosteroid use. A thin layer is applied to affected areas twice daily in the morning and evening. Oral Antihistamine (Cetirizine 10 mg):Cetirizine is a second-generation antihistamine that helps reduce itching (Vanderah, 2023). It is given in the evening to minimize potential sedative effects throughout the day. 10 mg once a day.Emollient Cream (Eucerin Advanced Repair Cream):Emollient creams help maintain skin hydration, reducing dryness and preventing future flare-ups (Vanderah, 2023). Eucerin Advanced Repair Cream is fragrance-free, minimizing the risk of additional allergens. It is applied liberally to affected areas as needed throughout the day. The route of application is topically. Short-Term Oral Steroid (Prednisone 20 mg):For severe cases of ACD, Prednisone provides rapid systemic anti-inflammatory effects (Vanderah, 2023). A short-term course minimizes the risk of systemic side effects. It is given in the dose of 40 mg once daily for three days, then 20 mg once daily for three days. It should be administered orally in the morning for a six-day course. EducationPatient education is critical in the comprehensive management of Allergic Contact Dermatitis (ACD), and a customized education plan for Mr. KG is designed to equip him with the knowledge and skills needed to identify and manage triggers, adhere to treatment regimens, and implement preventive measures. Understanding ACD:Provide extensive information regarding ACD, highlighting that it is an immune-mediated response to certain allergens upon skin contact and that symptoms may occur 48 to 72 hours after exposure. Identification of Allergens:Educate Mr. KG about common allergens, emphasizing the need to identify and avoid them. Discuss probable allergen sources, such as specific metals, scents, and plants, and provide resources on analyzing product labels for allergen presence. Patch Testing Results:Discuss the patch testing results, emphasizing positive reactions and their significance (Mahler et al., 2019). Discuss the allergens found and the need to avoid them to avoid future flare-ups. Skincare Practices:Provide recommendations on proper skincare habits, such as using fragrance-free and hypoallergenic products (Goh et al., 2022). Emphasize the significance of moisturization to maintain skin barrier integrity and limit the risk of future episodes. Topical Medication Application:Correctly demonstrate how to apply a topical corticosteroid (Clobetasol Propionate 0.05% Cream) (Moustafa et al., 2021). Emphasize the necessity of applying a thin coating solely to affected regions, avoiding normal skin, and thoroughly cleaning hands afterward. Emollient Use:Teach Mr. KG how to use an emollient cream (Eucerin Advanced Repair Cream) daily to maintain his skin moisturized, emphasizing the application to all areas prone to dryness, even if he is asymptomatic. Allergen Avoidance Strategies:Discuss practical allergen avoidance tactics such as wearing hypoallergenic jewelry, employing alternate perfumes, and exercising caution when exposed to potential triggers in the workplace. Follow-Up and Monitoring:Emphasize the significance of regular follow-up dermatologic consultations for continuing monitoring, therapy efficacy assessment, and treatment plan changes as appropriate. Lifestyle Modifications:Discuss potential lifestyle changes, such as changes in employment habits or personal care product selection, to reduce the chance of future allergen exposure. Emergency Action Plan:Provide guidance on spotting severe symptoms that may necessitate immediate medical assistance, and provide Mr. KG with an emergency action plan that includes contact information for medical professionals and the nearest healthcare institution. Non-medication treatmentsNon-medication treatments and medication are essential for effectively managing Allergic Contact Dermatitis (ACD). This comprehensive plan for Mr. KG emphasizes lifestyle changes and skincare practices aimed at reducing allergen exposure, alleviating symptoms, and preventing future flare-ups. Allergen Avoidance:Educate Mr. KG on identifying and avoiding specific allergens identified through patch testing. Provide resources on allergen-free alternatives in personal care products, jewelry, and occupational settings. If occupational exposure is a trigger, collaborate with Mr. KG to explore potential changes in his work environment or practices to minimize allergen contact. Clothing and Textile Considerations:To decrease irritation, advise Mr. KG to wear loose-fitting, breathable clothing made of natural fibers, such as cotton, and to wash garments and bed linens using fragrance-free and hypoallergenic detergents. Skincare Practices:Encourage Mr. KG to use mild, fragrance-free cleansers during bathing to avoid further irritation (Nassau & Fonacier, 2020). Suggest lukewarm water rather than hot water, which can exacerbate dryness. Stress the importance of regular moisturization with emollient cream (Eucerin Advanced Repair Cream) to maintain skin hydration and reinforce the skin barrier. Avoidance of Irritants:Inform Mr. KG to avoid products containing harsh chemicals, strong detergents, or excessive fragrances, as these substances can aggravate skin irritation. Emphasize the importance of not scratching, as it can worsen symptoms and lead to complications such as infection. Wear cotton gloves at night if itching is a concern. Cool Compresses:Apply cool compresses to affected regions to relieve irritation and inflammation (Patel & Nixon, 2022). Avoid using hot water or ice directly on the skin. Stress Management:Talk about the potential influence of stress on ACD symptoms and encourage stress-reduction practices like mindfulness, meditation, or hobbies to boost general well-being. Follow-Up Dermatologic Consultations:Emphasize the significance of regular follow-up dermatologic consultations for continuing monitoring and changes to the treatment and non-medication strategy based on the skin’s response.

|

Evaluation of patient encounterMr. KG’s recent patient encounter exemplifies a meticulous and patient-centered approach to managing his diagnosed Allergic Contact Dermatitis (ACD). The diagnostic process began with an in-depth exploration of his medical history and a thorough physical examination, focusing on the distinctive features of his skin condition (Bickley, 2020). The incorporation of patch testing proved instrumental in pinpointing specific allergens contributing to ACD, a patient-centric approach that The short-term course of oral prednisone was carefully dosed and scheduled, balancing the need for immediate anti-inflammatory effects with the cautious avoidance of potential side effects associated with prolonged saline administration. Mr. KG received detailed information on the nature of ACD, specific allergen identification, and practical strategies for allergen avoidance in daily life during the educational component of the encounter. Demonstrations on the correct application of prescribed medications ensured optimal adherence while providing an emergency action plan empowered Mr. KG to take proactive measures in the event of severe symptoms. Mr. KG was educated on textile considerations, skincare routines, and stress management techniques, acknowledging the potential impact of stress on ACD symptoms. The inclusion of regular follow-up dermatologic consultations underscores the dynamic nature of the care plan, allowing for ongoing monitoring and adjustments based on Mr. KG’s responses.

|

References FOR Sample of SOAP Notes Nursing #1

Bickley, L. (2020). Bates’ guide to physical examination and history taking (13th ed.). Wolters Kluwer Health. ISBN: 9781496398178

Foti, C., Bonamonte, D., Filoni, A., & Angelini, G. (2021). Patch testing. In Springer eBooks (pp. 499–527). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-49332-5_23

Garg, V., Brod, B. A., & Gaspari, A. A. (2021). Patch testing: Uses, systems, risks/benefits, and its role in managing the patient with contact dermatitis. Clinics in Dermatology, 39(4), 580–590. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clindermatol.2021.03.005

Goh, C. J., Wu, Y., Welsh, B., Abad-Casintahan, M. F., Tseng, C. J., Sharad, J., Jung, S., Rojanamatin, J., Sitohang, I. B. S., & Chan, H. N. K. (2022). Expert consensus on holistic skin care routine: Focus on acne, rosacea, atopic dermatitis, and sensitive skin syndrome. Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology, 22(1), 45–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocd.15519

Goolsby, M. J. & Grubbs, L. (2018). Advanced assessment: Interpreting findings and formulating differential diagnoses (4th ed.). F. A. Davis Company. ISBN: 9780803668942

Mahler, V., Nast, A., Bauer, A., Becker, D., Brasch, J., Breuer, K., Dickel, H., Drexler, H., Elsner, P., Geier, J., John, S. M., Kreft, B., Köllner, A., Merk, H. F., Ott, H., Pleschka, S., Portisch, M., Spornraft‐Ragaller, P., Weißhaar, E., Uter, W. (2019). S3 guidelines: Epicutaneous patch testing with contact allergens and drugs – Short version, Part 1. Journal Der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft, 17(10), 1076–1093. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddg.13956

Moustafa, D., Neale, H., Ostrowski, S. M., Gellis, S. E., & Hawryluk, E. B. (2021). Topical corticosteroids for noninvasive treatment of pyogenic granulomas. Pediatric Dermatology, 38(S2), 149–151. https://doi.org/10.1111/pde.14698

Nassau, S., & Fonacier, L. (2020). Allergic contact dermatitis. Medical Clinics of North America, 104(1), 61–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2019.08.012

Patel, K., & Nixon, R. (2022). Irritant contact dermatitis — a review. Current Dermatology Reports, 11(2), 41–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13671-021-00351-4

Tanahashi, T., Sasaki, K., Numata, M., & Matsunaga, K. (2019). Three cases of photoallergic contact dermatitis induced by the ultraviolet absorber benzophenone that occurred after dermatitis due to ketoprofen‐Investigation of cosensitization with other ultraviolet absorbers and patient background. Journal of Cutaneous Immunology and Allergy, 2(5), 139–147. https://doi.org/10.1002/cia2.12080

Vanderah, T. W. (2023). Katzung’s Basic and Clinical Pharmacology, 16th Edition. McGraw-Hill Education / Medical.

Sample of SOAP Notes Nursing #2

Subjective, Objective, Assessment, Plan (SOAP) Notes

Patient Information:

Initials: J.D., Age: 15, Sex: Male, Race: Caucasian

Socio-economic Status: J.D. is fully dependent on his family’s resources

SUBJECTIVE

Chief Complaint:

John Doe, a 15-year-old male, presents to the Dermatology clinic at his dad’s company. On a close examination of the patient, he says, “I have a red itchy rash on my arms and legs.”

History of Present Illness:

A 15-year-old Caucasian male, J.D., presented with a red, itchy rash that began approximately one week ago. He describes the location of the rash as primarily on the arms and legs. The character of the rash is red, raised, and intensely itchy. He has not noticed any associated symptoms, such as fever or joint pain. The itching is worse at night and seems to be exacerbated by heat and physical activities, and is slightly relieved by over-the-counter hydrocortisone cream. He rates the severity of the itching as a 6/10 on the pain scale.

Location: arms and legs

Onset: One week ago

Character: Red, raised, and intensely itchy rash

Associated signs and symptoms: No fever or joint pain

Timing: At night

Exacerbating/Relieving factors:

This seems to be exacerbated by heat and physical activities and is slightly relieved by over-the-counter hydrocortisone cream.

Severity:

6/10

Current Medications:

Albuterol inhaler as needed for exercise-induced asthma.

Allergies:

No known drug allergies. Environmental allergies include dust mites and ragweed, which cause mild seasonal rhinitis.

Past Medical History:

Asthma diagnosed at age 7, up to date on all immunizations, including most recent tetanus shot in 2020.

Past Surgical History (PSH):

No prior surgeries or past major illnesses.

Soc & Substance History:

JD is a high school student who enjoys playing soccer and video games. He lives with both parents and a younger sibling. He denies smoking, drinking, or using recreational drugs. JD wears a seatbelt regularly and has a working smoke detector in his home.

Fam History:

Father with eczema, mother with hay fever. One paternal uncle has psoriasis.

Surgical History:

None.

Mental History:

No history of mental health concerns or self-harm.

Violence History:

No concerns about safety.

Reproductive History:

JD is not sexually active.

OBJECTIVE DATA

ROS

GENERAL:

No weight loss, fever, chills, weakness, or fatigue.

HEENT:

No hearing loss, sneezing, congestion, runny nose, or sore throat.

SKIN:

Rash and itching.

CARDIOVASCULAR:

No chest pain or edema.

RESPIRATORY:

No shortness of breath or cough.

GASTROINTESTINAL:

No anorexia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, or abdominal pain. NEUROLOGICAL: No headache, dizziness, syncope, paralysis, ataxia, numbness, or tingling in the extremities.

MUSCULOSKELETAL:

No muscle pain, back pain, joint pain, or stiffness.

HEMATOLOGIC:

No anemia, bleeding, or bruising.

LYMPHATICS:

No enlarged nodes.

PSYCHIATRIC:

No history of depression or anxiety.

ENDOCRINOLOGIC:

No reports of sweating, cold or heat intolerance, polyuria, or polydipsia.

REPRODUCTIVE:

Not sexually active.

ALLERGIES:

History of asthma, environmental allergies to dust mites, and ragweed.

ASSESSMENT

O.

Physical exam

General:

Well-appearing, alert, and oriented adolescent male.

Head:

Normocephalic and atraumatic.

EENT:

PERRL, EOMI. TMs clear bilaterally. Nares patent without discharge. Oropharynx is moist and clear.

Skin:

Erythematous, raised patches of skin with a scratched appearance are noted on the arms and legs.

Cardiovascular:

Regular rate and rhythm. No murmurs.

Respiratory:

Clear to auscultation bilaterally.

Musculoskeletal:

Full range of motion in all extremities. No joint swelling or tenderness.

Diagnostic results:

None at this time.

A.

- Atopic Dermatitis (Eczema) – ICD-10 L20.9: JD’s symptoms of a red, itchy rash on the extremities, along with a personal history of asthma and a family history of eczema support this as the most likely diagnosis (Chovatiya & Silverberg, 2019).

- Contact Dermatitis – ICD-10 L25.9: This could also present as an itchy, red rash (Mansilla-Polo et al., 2023). However, it is less likely, given the distribution of the rash and JD’s history (Larese Filon et al., 2023).

- Psoriasis – ICD-10 L40.9: Given the family history, psoriasis could be considered, but JD’s symptoms are more suggestive of eczema (Snyder et al., 2023).

P.

In order to manage JD’s dermatological complaint effectively, a specific treatment plan has been formulated based on his current condition (Walden University, 2019). The cornerstone of his management involves the application of triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.1%, a medium-strength corticosteroid known for its potent anti-inflammatory and antipruritic effects (van Heugten et al., 2018). JD has been instructed to apply this medication judiciously to the areas of skin manifesting the rash, adhering to a twice-daily regimen for a duration of two weeks (Stevens et al., 2014). Simultaneously, the importance of incorporating daily skin moisturization into his routine has been emphasized, as maintaining optimal skin hydration can significantly alleviate the symptoms of dryness and itchiness associated with his condition (Dr. Zenn, 2013). It is recommended to use a hypoallergenic, fragrance-free moisturizing cream to prevent any potential allergic reactions (Thompson et al., 2020).

Furthermore, JD has been counseled on pertinent lifestyle modifications that can aid in managing his condition. These include avoiding known triggers that may exacerbate his symptoms, such as exposure to excessive heat and engaging in strenuous physical activity, which can lead to increased perspiration and, subsequently, heightened skin irritation (Stevens et al., 2014). Moreover, maintaining short, neatly trimmed nails has been advised to prevent inadvertent skin abrasion or laceration stemming from intense scratching.

After initiating this management plan, a follow-up appointment will be scheduled for three weeks. The appointment will enable the healthcare team to evaluate JD’s progress and assess his clinical response to the treatment (Leasure & Cohen, 2023). In the event that his symptoms persist or worsen, consideration will be given to a referral to a dermatology specialist for further assessment and potentially more targeted treatment interventions (Larese Filon et al., 2023). This comprehensive approach aims to ensure that JD’s dermatological health is meticulously cared for, offering him the best chance at an improved quality of life.

Reflection

In evaluating the treatment plan for John Doe (JD), a 15-year-old male presenting with atopic dermatitis, I found myself in agreement with the selected course of action (Chu, 2020). The decision to prescribe a topical corticosteroid is an evidence-based, first-line treatment option for managing symptoms of atopic dermatitis, such as pruritus and inflammation. This class of medication works by reducing inflammation and suppressing the immune response, thereby mitigating the severity of JD’s symptoms. It is anticipated that, with consistent application, JD’s discomfort will be significantly alleviated, improving his quality of life.

One fascinating part of JD’s situation was the visible illustration of the ‘allergic triad’ or ‘atopic triad.’ This concept explains the simultaneous presence of three conditions: atopic dermatitis (eczema), asthma, and allergic rhinitis (Chovatiya & Silverberg, 2019). Given JD’s past with asthma, he was more likely to develop eczema, the skin condition within this group of related conditions (Dr. Zenn, 2013). The interaction between these different body systems highlights how the immune system works as a whole and emphasizes the need for a well-rounded look at a patient’s health history and treatment.

Should JD have insurance, it would enable us to consider an extensive array of treatments, which might include cutting-edge biologics for severe eczema and potentially mental health services (Donley & Kiraly, 2019). However, if JD lacked insurance, we would need to prioritize cost-effective strategies, like over-the-counter creams and lifestyle or environmental adjustments to manage his condition (Donley & Kiraly, 2019). In addition, we could investigate the potential for assistance from programs like CHIP or Medicaid for those without insurance.

As a Washington D.C. resident, JD can avail numerous local services. This encompasses clinics affiliated with George Washington University, catering to patients lacking comprehensive insurance. JD might also find value in joining support circles for adolescent eczema patients led by entities like the National Eczema Association. Moreover, the city’s Department of Health and Human Services could assist JD’s family in exploring public aid options. Programs like Healthy Schools DC could assist in managing related conditions such as asthma and allergies at school, indirectly contributing to controlling JD’s atopic dermatitis.

If I meet a patient with a similar case in the future, I would give the same amount of attention to detail while assessing them and coming up with a treatment plan. Nevertheless, I would include a more in-depth look into how JD interacts with his environment and lifestyle habits. Patients with eczema often react to specific triggers, so understanding what JD comes in contact with that could potentially cause irritation is key to managing his condition long-term (Leasure & Cohen, 2023). This could involve common things around the house, like pet hair, certain types of laundry soap, or even some materials he regularly comes into contact with. Being aware of these things can help us educate the patient and come up with ways to avoid flare-ups.

On top of that, I would want to understand the emotional effects of his condition. Having eczema can make a teenager feel self-conscious and stressed, which can accidentally make the condition worse. A mental health check and making sure JD has the support he needs are crucial for a well-rounded care approach. By tweaking how we approach things, we hope to provide care focused on the patient, with the main goal of managing JD’s symptoms and enhancing his overall quality of life.

References FOR Sample of SOAP Notes Nursing #2

Chovatiya, & Silverberg. (2019). Pathophysiology of atopic dermatitis and psoriasis: implications for management in children. Children, 6(10), 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/children6100108

Chu, C.-Y. (2020). Treatments for childhood atopic dermatitis: an update on emerging therapies. Clinical Reviews in Allergy & Immunology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12016-020-08799-1

Donley, S. R., & Kiraly, C. (2019). The impact of the political and policy cultures of Washington, DC, on the Affordable Care Act. Annual Review of Nursing Research, 37(1), 187–207. https://doi.org/10.1891/0739-6686.37.1.187

Dr. Zenn (2013, November 20). Learn How to Suture – Best Suture Techniques and Training. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TFwFMav_cpE

Larese Filon, F., Maculan, P., Crivellaro, M. A., & Mauro, M. (2023). Effectiveness of a skincare program with a cream containing ceramide c and personalized training for secondary prevention of hand contact dermatitis. Dermatitis: Contact, Atopic, Occupational, Drug, 34(2), 127–134. https://doi.org/10.1089/derm.2022.29002.flf

Leasure, A. C., & Cohen, J. M. (2023). Prevalence of eczema among adults in the United States: a cross-sectional study in the All of Us research program. Archives of Dermatological Research, 315(4), 999–1001. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00403-022-02328-0

Mansilla-Polo, M., Navarro-Mira, M. Á., & Botella-Estrada, R. (2023). [Contact dermatitis by face mask]. Medicina Clinica, 160(12), 566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medcli.2023.01.004

Snyder, A. M., Brandenberger, A. U., Taliercio, V. L., Rich, B. E., Webber, L. B., Beshay, A. P., Biber, J. E., Hess, R., Rhoads, J. L. W., & Secrest, A. M. (2023). Quality of life among family of patients with atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 30(3), 409–415. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-022-10104-7

Stevens, D. L., Bisno, A. L., Chambers, H. F., Dellinger, E. P., Goldstein, E. J. C., Gorbach, S. L., Hirschmann, J. V., Kaplan, S. L., Montoya, J. G., & Wade, J. C. (2014). Executive summary: practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the infectious diseases society of America. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 59(2), 147–159. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciu444

Thompson, A. M., Chan, A., Torabi, M., Kromenacker, B., Price, K. N., Hsiao, J. L., & Shi, V. Y. (2020). Eczema moisturizers: Allergenic potential, marketing claims, and costs. Dermatologic Therapy, 33(6), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.14228

van Heugten, A. J. P., de Vries, W. S., Markesteijn, M. M. A., Pieters, R. J., & Vromans, H. (2018). The role of excipients in the stability of triamcinolone acetonide in ointments. AAPS PharmSciTech: An Official Journal of the American Association of Pharmaceutical Scientists, 19(3), 1448–1453. https://doi.org/10.1208/s12249-018-0957-8

Walden University. (2019). MSN nurse practitioner practicum manual https://academicguides.waldenu.edu/fieldexperience/son/formsanddocuments

Sample of SOAP Notes Nursing #3

Subjective, Objective, Assessment, Plan (SOAP) Notes

Student Name: B.B. |

Course: |

||||||

Patient Name: M.G. |

Date: 00-00-00 |

Time: |

|||||

Ethnicity: Filipinos |

Age: 00 |

Sex: Female |

|||||

SUBJECTIVE |

|||||||

Chief Complaint (CC):“I have vaginal discharges with itching for 3 weeks now.” |

|||||||

History of Present Illness (HPI):B.B. is a 65-year-old Filipino woman with a chief complaint of discharge from the genital area accompanied by long-lasting itching that started 3 weeks ago. She states that she noticed about 3 weeks ago an abnormal vaginal discharge with white color and thick consistency. She also recounts an associated symptom of vaginal discharge and intermittent itching, particularly at night. She says, however, that as days passed, there was no significant improvement in her symptoms. She denies experiencing symptoms such as urinary frequency, dysuria, pelvic pain, or abnormal vaginal bleeding are alien to her. In addition, she has no systemic symptoms, including fever, chills, or discomfort. She notes that no aggravating factors are worsening her symptoms except for the itching, which worsens at night. On the other hand, no alleviating factors relieve her discomfort. Mrs. M.G. took the step of avoiding any form of self-treatment and decided to seek medical help as she was experiencing persistent symptoms. |

|||||||

Medications:None mentioned. |

|||||||

Allergies:No known food and drug allergies Medication Intolerances:None mentioned Past Medical History (PMH)There is no history of previous chronic illnesses or significant traumas experienced by the patient. She had a previous diagnosis of appendicitis in June 2017, having complained about strong pain in the umbilicus area and the right abdominal region. Hospitalizations/Surgeries:Appendicitis, 1987 Surgery:Appendectomy, 1990 |

|||||||

FAMILY HISTORY |

|||||||

M (Mother):Died at 84 years old from complications of TB. MGM (Maternal Grandmother):Died at the age of 98 from complications of type 2 diabetes. MGF (Maternal Grandfather):Died at the age 101 after having complications of myocardial infarction. F (Father):Currently alive, aged 93 years, with a history of depression and lung cancer. PGM (Paternal Grandmother):Died at 94 years old due to complications of pneumonia. PGF (Paternal Grandfather):Died at 99 years of age due to prostate cancer. |

|||||||

Social History:The patient is a married woman employed as a teacher. She lives with her husband and two children. Does not smoke or use tobacco. She verbalizes that she does not use any recreational drugs or illicit substances. There is no recent travel history. Her social support group includes family, friends, and siblings. Tobacco Use:She is a non-smoker. Alcohol Use:She is a non-alcoholic. Illegal Substance:She does not use any illicit substances. She does not use any recreational drugs. Marital Status:Married. Sexual Activity:She is sexually active Gender Identity:Female Sexual Orientation:She is heterosexual Occupation:She works as a teacher in a local high school. Nutrition History:She has an optimal nutritional status. Family Support:Her social support group includes family, friends, and siblings. LMP:2004. She has been having a regular menstrual cycle since her first menarche at the age of 13 years. |

|||||||

REVIEW OF SYSTEMS |

|||||||

General:Denies fever, chills, and weight loss. |

Cardiovascular:Denies chest pain, palpitations. |

||||||

Skin:Denies rash, lesions, or changes in skin color. |

Respiratory:Denies cough, wheezing, and shortness of breath. |

||||||

Eyes:Denies vision changes and eye pain. |

Gastrointestinal:Denies abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea. |

||||||

Ears:Denies ear pain, discharge, hearing loss, or tinnitus. |

Genitourinary/Gynecological:+Vaginal discharges with itching. Denies having a history of urinary infection. + Increased frequency and urgency. |

||||||

Nose/Mouth/Throat:Denies nasal congestion, sore throat, or difficulty swallowing. |

Musculoskeletal:Denies joint pain and stiffness. |

||||||

Neurological:Denies headache, dizziness, numbness or weakness. |

Heme/Lymph/Endo:Denies bleeding disorders and lymphadenopathy. |

||||||

Psychiatric:Denies depression and anxiety. |

Breast:Denies breast pain. Denies abnormal nipple discharge. |

||||||

OBJECTIVE |

|||||||

| Weight:

62 kg |

Height: 155 cm |

BMI: 25.81 | BP: 117/78mmHg | Temp: 98.1°F | Pulse: 77 b/m | Resp: 18 b/m | |

General Appearance:The patient appears well-nourished and healthy. Appears to be in no acute distress. |

|||||||

Skin:Warm and dry; no rashes or lesions noted |

|||||||

HEENT:The head is normocephalic and atraumatic. There are no abnormalities observed. |

|||||||

Cardiovascular:Regular rate and rhythm, no murmurs, rubs, or gallops. The S1 and S2 sounds are heard. |

|||||||

Respiratory:Rhythmic movement of the chest wall during inhalation and exhalation. Clear to auscultation bilaterally, no wheezing or crackles. |

|||||||

Gastrointestinal:The abdomen appears to be flat in shape. Soft, non-tender, and non-distended. There is a bowel sound in all quadrants. No hepatosplenomegaly or masses were palpated. |

|||||||

Genitourinary/ Gynaecology:External Genitalia:The vulva looks pale and dry. Labia minora is thinner and less elastic. The clitoris is less sensitive to touch compared to normal. Vaginal Examination:The vaginal mucosa appears pale, dry, and thin. The vaginal walls are weak and friable, with areas of easy bleeding upon contact. Whitish, thick vaginal discharge was observed in the vagina. Pale, dry mucosa with no erythema or lesions noted Vaginal pH Measurement:The vaginal pH is high (>4.5). Pelvic Examination:The uterus is smaller, with reduced mobility. Ovaries appear normal without any masses or tenderness when palpated. Urethral Examination:Urethral meatus looks pale and has a dry surface, and there are the symptoms of inflammation. Patient reports tenderness upon palpation of the urethra. Bladder Examination:Bladder is palpable and non-tender. Perineal Examination:Perineal skin tends to get dry and may manifest irritation on it. The pelvic floor muscles show decreased tone and strength. |

|||||||

Musculoskeletal:Complete range of motion on all limbs. No deformities or swelling on joints were detected during the examination. |

|||||||

Breast:No masses or abnormal discharge. |

|||||||

Neurological:Alert and oriented to time, place, and person. No focal deficits were observed throughout the examination. All the cranial nerves from I to XII are intact and function optimally. |

|||||||

Psychiatric:The patient is concerned about her vaginal discharge. The patient maintains eye contact throughout the examination. A fully cooperative and easy rapport was established after the examination started. |

|||||||

Lab Tests:None ordered. |

|||||||

Special Tests:None ordered. |

|||||||

DIAGNOSIS (minimum required differential and presumptive dx, can do more) |

|||||||

Differential Diagnoses1. Candidal Vulvovaginitis (B37.3):Candidal vulvovaginitis, commonly known as a yeast infection, is a fungal disease caused by Candida species, often Candida albicans (De Cássia et al., 2021). It usually exhibits symptoms of vaginal itching, burning, and discharges that are not normal. The discharge, in many cases, is described as being thick, white, and cottage cheese-like in appearance. The subjective data shows that a chief differential diagnosis is yeast infection characterized by 3 weeks of white discharge and itching. The patient reported that discharge color and thickness match the ones observed in candidal vulvovaginitis. Besides that, itching in the vagina can also be a typical sign of this illness (Woelber et al., 2020). By looking at the vaginal mucosa objectively, it may appear erythematous and edematous, which also support the diagnosis. Under the microscope, the discharge is tested for yeast cells and pseudohyphae, which provide definitive evidence for candidal vulvovaginitis. 2. Bacterial Vaginosis (N76.0):Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is the most frequent vaginal infection that is associated with a disruption in the normal vaginal flora with the consequent overgrowth of anaerobic bacteria, particularly Gardnerella vaginalis (Morrill et al., 2020). This condition is usually characterized by a foul-smelling, thin, greyish-white vaginal discharge, which can have a “fishy” odor. Taking into account only subjective data focused on vaginal discharges but not on odor, the most probable differential diagnosis is bacterial vaginosis. Although the patient did not report an odor associated with the discharge, it is essential to note that bacterial vaginosis might also appear without any odor to the patient in some instances. On objective inspection, vaginal discharge can be identified as white, thick, and grayish, accompanied with an elevated vaginal pH. A “whiff” test using potassium hydroxide may produce a typical fishy smell, letting us confirm the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis (Swidsinski et al., 2023). 3. Trichomoniasis (A59.0):Trichomoniasis is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the protozoan parasite Trichomonas vaginalis (Rigo et al., 2022). The features like frothy yellow-green vaginal discharge, itching of the vagina, and dysuria usually characterize it. However, it is possible in some cases to be asymptomatic. Although the subjective data in the SOAP note does not explicitly refer to the typical frothy, yellow-green discharge featured in trichomoniasis, this symptom is consistent with the complaint of vaginal discharges with itching. Not all people will develop the standard symptoms recognized for this condition (Van Der Pol et al., 2021). After precisely observing a microscopic analysis of the discharge from the vagina, the motile trichomonads can be seen, which is the definitive evidence that the trichomoniasis is present. Besides this, nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) may be carried out for confirmation when microscopic examination cannot provide the answer.

|

Presumptive Diagnosis (ICD 10 codePostmenopausal atrophic vaginitis (N95.2)Postmenopausal atrophic vaginitis is a condition that leads to inflammation, thinning, and drying of the vaginal walls due to estrogenic deficiency after menopause (Pérez‐López et al., 2021a). This disorder is frequently manifested with a variety of symptoms, which are related to vaginal mucosal changes, such as vaginal dryness, itching, burning, dyspareunia (painful intercourse), and sometimes abnormal vaginal discharge. Generally, symptoms begin after menopause takes effect, and estrogen starts to drop in levels which additionally leads to changes in vaginal epithelium and lubrication as well as higher susceptibility to infections and discomfort (Pérez‐López et al., 2021b). Because of subjective symptoms such as vaginal discharge and itching for the past 3 weeks in a 65-year-old postmenopausal female, there is reason to conclude that postmenopausal atrophic vaginitis is a possible diagnosis (Zheng et al., 2021). The age and menopausal status of the patient are vital risk factors to take into account, as there is a fall in estrogen levels after menopause, and this results in vaginal mucosa changes. The subjective complaints of vaginal itching are coinciding with the common symptoms of postmenopausal atrophic vaginitis, illustrating the core inflammation and irritation of the vaginal mucosa. When an exam was done objectively, there was a finding that a woman had pale, dry, and thin vaginal mucosa, which was consistent with postmenopausal atrophic vaginitis. Vaginal walls might seem like they are very delicate and could easily be subjected to trauma because of the hormonal changes at the tissue level. Furthermore, the pH of the vagina may be changed (> 4.5) as a result of changes in the microenvironment of the vagina, which may aggravate symptoms such as itching and discomfort (Lin et al., 2021). The findings of these objective data support the diagnostic basis of postmenopausal atrophic vaginitis and enhance understanding of the pathophysiology triggering the patient’s symptoms. |

||||||

Plan/Therapeutics:Confirmation of Diagnosis:Conduct a complete physical examination to determine the appearance of vaginal mucosa and the pH level (Tanmahasamut et al., 2020). Perform vaginal swabs for microscopy, culture, and sensitivity to find atrophic changes and to exclude other potential infections. Hormonal Therapy:You prescribe topical estrogen therapy, for example, a 0.5 to 2 g of Premarin cream administration intravaginally once a day for 1 to 2 weeks, followed by a maintenance dose of 0.5 g 1 to 3 times a week for several months to years as needed (Vanderah, 2023). Non-Hormonal Measures:Encourage the use of non-hormonal vaginal moisturizers and lubricants, which enhance vaginal moisture and decrease intercourse discomfort (Shim et al., 2021). Non-hormonal alternatives, such as Replens vaginal moisturizer, should be applied into the vagina as required for symptom relief, usually every 2 to 3 days or before sex, and may be used continuously for management. Symptomatic Relief:Antifungal agents such as clotrimazole cream are prescribed. These antifungal agents are applied intravaginally once daily for 7 to 14 days, and the length of treatment is determined by the severity and response to therapy for the yeast infection (Vanderah, 2023). Follow-Up and Monitoring:Make a follow-up appointment in 2 to 4 weeks to monitor the patient’s reaction to the treatment and make further adjustments, if necessary (Seferovic et al., 2020). Look for any improvement, like the amount of discharges, itching, and pain during intercourse. Patient Education:Specific components include educating the patient about long-term treatment for atrophic vaginitis (Domoney et al., 2020). Identify probable advantages/disadvantages of HRT and remove any fears or misunderstandings the patient may have. Referral to Specialist:If the patient does not respond favorably to conservative therapy or is suspected of gynecology diseases, a gynecologist or urogynecologist should be referred for further workup and treatment (Kawaguchi et al., 2020). Psychological Support:Psychosocial support and psychological reassurance should be provided to deal with any emotional distress or concerns sparked by the symptoms and their role in the quality of life. Provide the group with necessary resources for support groups and counseling services if required (Ohta et al., 2023). |

|||||||

Diagnostics:Patient History and Symptoms Assessment:Perform a thorough medical history interview, paying special attention to menopausal status, previous gynecological conditions, and current complaints, such as the duration and nature of the vaginal discharge and itching (Neal et al., 2020). Explore whether some aggravating factors or recent changes in the medication plan could be responsible for the symptoms. Physical Examination:Conduct a detailed pelvic exam to note the vaginal mucosa’s appearance, including signs of atrophy like pallor, dryness, and thinning (Murina et al., 2023). Examine for any other symptoms like vulvar erythema, edema, or dyspareunia (painful intercourse). Vaginal pH Measurement:Get a pH indicator strip or pH meter to measure precisely the acidity of the vaginal secretions (Bumphenkiatikul et al., 2020). Atypical vaginitis after menopause is called atrophic vaginitis, which is marked by an increased pH of the vagina (>4.5), which is due to changes in the vaginal microenvironment caused by low estrogen levels. Vaginal Swab for Microscopy, Culture, and Sensitivity:Get a vaginal swab to collect a sample of vaginal discharge for laboratory tests (Baek et al., 2021). Microscopic inspection can expose clue cells (characteristic of bacterial vaginosis), yeast cells, or Trichomonas vaginalis (characteristic of trichomonal infection). Culture and sensitivity testing can be useful in finding specific pathogens and picking up the proper antimicrobial therapy if necessary. Nucleic Acid Amplification Tests (NAATs):Conduct NAATs, like PCR testing, looking out for the presence of Trichomonas vaginalis DNA in vaginal mucus samples (Van Gerwen et al., 2022). NAATs have high sensitivity and specificity, which makes them applicable for trichomoniasis diagnoses, especially when microscopic evaluation is inconclusive (Fantasia et al., 2020). Histological Examination:A biopsy of the vaginal mucosa is recommended if there are suspicions of malignancy or some other pathological condition (Crean-Tate et al., 2020). Histological examination may be useful to detect the amount of vaginal atrophy and the presence of inflammatory changes. Laboratory Tests:Additional laboratory tests are performed when necessary, guided by the clinical suspicion and differential diagnosis. Such examinations might be complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and serum hormone levels (e.g., estradiol, follicle-stimulating hormone) to assess hormone status and rule out some systemic conditions causing vaginal symptoms (De Seta et al., 2021). |

|||||||

Education Provided:Understanding Postmenopausal Atrophic Vaginitis:Describe the pathophysiology of postmenopausal atrophic vaginitis focusing on the mechanism that produces vaginal mucosal changes, which is the reducing estrogen levels (De Oliveira et al., 2022). Educate the patient on common symptoms such as vaginal dryness, itching, burning, and dyspareunia. Tell the patient these symptoms are common and treatable (Cash, 2023). Hormonal Changes and Vaginal Health:Discuss the effects of menopause on vaginal health, considering the decline in estrogen levels and their impact on vaginal lubrication and tissue integrity (Costa et al., 2021). Emphasize that there are ways to maintain vaginal health through HRT or other treatments to alleviate symptoms and stop complications from happening. Treatment Options:Let the patient know about the different treatment options for postmenopausal atrophic vaginitis, like hormonal therapy (such as estrogen creams, tablets, or vaginal rings), as well as non-hormonal options like vaginal moisturizers and lubricants. Talk about the benefits, risks, and possible side effects of different treatment alternatives so the patient can choose wisely (Vanderah, 2023). Vaginal Hygiene Practices:Teach the patient how to practice good vaginal hygiene to avoid vaginal problems and irritation. Explain why women should not try to use perfumed soaps, douches, or other harsh products to maintain the vaginal pH because they worsen symptoms (Holdcroft et al., 2023). Sexual Health and Intercourse:Discuss concerns about sexual intercourse and intimacy, which include discomfort or pain resulting from vagina dryness and atrophy (Cagnacci et al., 2019). Explain ways to better sexual comfort, including the use of water-based lubricants and sexual activities that avoid friction and discomfort (Fantasia et al., 2020). |

|||||||

References for Sample of SOAP Notes Nursing #3

Baek, J., Jo, H., Lee, S., Park, J., Cho, I., & Sung, J. H. (2021). Prevalence of Pathogens and Other Microorganisms in Premenopausal and Postmenopausal Women with Vulvovaginal Symptoms: A Retrospective Study in a Single Institute in South Korea. Medicina, 57(6), 577. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57060577

Bumphenkiatikul, T., Panyakhamlerd, K., Chatsuwan, T., Ariyasriwatana, C., Suwan, A., Taweepolcharoen, C., & Taechakraichana, N. (2020). Effects of vaginal administration of conjugated estrogens tablet on sexual function in postmenopausal women with sexual dysfunction: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. BMC Women’s Health, 20(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-020-01031-4

Cagnacci, A., Venier, M., Xholli, A., Paglietti, C., & Caruso, S. (2019). Female sexuality and vaginal health across the menopausal age. Menopause (New York, N.Y.), 27(1), 14–19. https://doi.org/10.1097/gme.0000000000001427

Cash, J. C. (2023). Family Practice Guidelines (6th ed.). Springer Publishing Company. ISBN: 9780826173546

Costa, A. P. F., Sarmento, A. C. A., Vieira‐Baptista, P., Eleutério, J., Cobucci, R. N., & Gonçalves, A. K. (2021). Hormonal approach for postmenopausal vulvovaginal atrophy. Frontiers in Reproductive Health, 3. https://doi.org/10.3389/frph.2021.783247

Crean-Tate, K., Faubion, S. S., Pederson, H. J., Vencill, J. A., & Batur, P. (2020). Management of genitourinary syndrome of menopause in female cancer patients: a focus on vaginal hormonal therapy. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 222(2), 103–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2019.08.043

De Cássia Orlandi Sardi, J., Silva, D. R., Aníbal, P. C., De Campos Baldin, J. J. C. M., Ramalho, S. R., Rosalen, P. L., Macedo, M. L. R., & Höfling, J. F. (2021). Vulvovaginal candidiasis: epidemiology and risk factors, pathogenesis, resistance, and new therapeutic options. Current Fungal Infection Reports, 15(1), 32–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12281-021-00415-9

De Oliveira, N. S., De Lima, A. B. F., De Brito, J. C. R., Sarmento, A. C. A., Gonçalves, A. K., & Eleutério, J. (2022). Postmenopausal vaginal microbiome and microbiota. Frontiers in Reproductive Health, 3. https://doi.org/10.3389/frph.2021.780931

De Seta, F., Caruso, S., Di Lorenzo, G., Romano, F., Mirandola, M., & Nappi, R. E. (2021). Efficacy and safety of a new vaginal gel for the treatment of symptoms associated with vulvovaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: A double-blind randomized placebo-controlled study. Maturitas, 147, 34–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2021.03.002

Domoney, C., Short, H., Particco, M., & Panay, N. (2020). Symptoms, attitudes and treatment perceptions of vulvo-vaginal atrophy in UK postmenopausal women: Results from the REVIVE-EU study. Post Reproductive Health, 26(2), 101–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053369120925193

Fantasia, H. C., PhD, R.N., WHNP-BC, Harris, A. L., PhD, R.N., WHNP-BC, & Fontenot, H. B., Ph (2020). Guidelines for Nurse Practitioners in Gynecologic Settings (12th ed.). Springer Publishing Company. ISBN: 9780826173263

Holdcroft, A. M., Ireland, D. J., & Payne, M. S. (2023). The Vaginal Microbiome in Health and Disease—What role do common intimate hygiene practices play? Microorganisms, 11(2), 298. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms11020298

Kawaguchi, R., Matsumoto, K., Ishikawa, T., Ishitani, K., Okagaki, R., Ogawa, M., Oki, T., Ozawa, N., Kawasaki, K., Kuwabara, Y., Koga, K., Sato, Y., Takai, Y., Tanaka, K., Tanebe, K., Terauchi, M., Todo, Y., Nose‐Ogura, S., Noda, T., Kobayashi, H. (2020). Guideline for Gynecological Practice in Japan: Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Japan Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 2020 edition. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research, 47(1), 5–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/jog.14487

Lin, Y., Chen, W., Cheng, C., & Shen, C. (2021). Vaginal pH value for clinical diagnosis and treatment of common vaginitis. Diagnostics, 11(11), 1996. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11111996

Morrill, S. R., Gilbert, N. M., & Lewis, A. L. (2020). Gardnerella vaginalis as a Cause of Bacterial Vaginosis: Appraisal of the Evidence From in vivo Models. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2020.00168

Murina, F., Torraca, M., Graziottin, A., Nappi, R. E., Villa, P., & Çetin, İ. (2023). Validation of a clinical tool for vestibular trophism in postmenopausal women. Climacteric, 26(2), 149–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/13697137.2023.2171287

Neal, C. M., Kus, L. H., Eckert, L. O., & Peipert, J. F. (2020). Noncandidal vaginitis: a comprehensive approach to diagnosis and management. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 222(2), 114–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2019.09.001

Ohta, H., Hatta, M., Ota, K., Yoshikata, R., & Salvatore, S. (2023). An online survey on coping methods for genitourinary syndrome of menopause, including vulvovaginal atrophy, among Japanese women and their satisfaction levels. BMC Women’s Health, 23(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-023-02439-4

Pérez‐López, F. R., Phillips, N., Vieira‐Baptista, P., Cohen-Sacher, B., Fialho, S. C. a. V., & Stockdale, C. K. (2021). Management of postmenopausal vulvovaginal atrophy: recommendations of the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease. Gynecological Endocrinology, 37(8), 746–752. https://doi.org/10.1080/09513590.2021.1943346

Pérez‐López, F. R., Vieira‐Baptista, P., Phillips, N., Cohen-Sacher, B., Fialho, S. C. a. V., & Stockdale, C. K. (2021). Clinical manifestations and evaluation of postmenopausal vulvovaginal atrophy. Gynecological Endocrinology, 37(8), 740–745. https://doi.org/10.1080/09513590.2021.1931100

Rigo, G. V., Frank, L. A., Galego, G. B., Santos, A. L. S. D., & Tasca, T. (2022). Novel Treatment Approaches to Combat Trichomoniasis, a Neglected and Sexually Transmitted Infection Caused by Trichomonas vaginalis: Translational Perspectives. Venereology, 1(1), 47–80. https://doi.org/10.3390/venereology1010005

Seferovic, A., Jamalyaria, S., Larsen, D. A., & Walker, D. N. (2020). In menopausal women with atrophic vaginitis, do nonhormonal treatments reduce symptoms as much as hormonal treatments? Evidence-based Practice, 23(9), 17–18. https://doi.org/10.1097/ebp.0000000000000775

Swidsinski, S., Moll, W. M., & Swidsinski, A. (2023). Bacterial vaginosis—vaginal polymicrobial biofilms and dysbiosis. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.m2023.0090

Tanmahasamut, P., Jirasawas, T., Laiwejpithaya, S., Areeswate, C., Dangrat, C., & Silprasit, K. (2020). Effect of estradiol vaginal gel on vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: A randomized double‐blind controlled trial. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research, 46(8), 1425–1435. https://doi.org/10.1111/jog.14336

Van Der Pol, B., Rao, A., Nye, M. B., Chavoustie, S., Ermel, A., Kaplan, C., Eisenberg, D. L., Chan, P. A., Mena, L., Pacheco, S., Waites, K. B., Xiao, L., Krishnamurthy, S., Mohan, R., Bertuzis, R., McGowin, C. L., Arcenas, R., Marlowe, E. M., & Taylor, S. N. (2021). Trichomonas vaginalis Detection in Urogenital Specimens from Symptomatic and Asymptomatic Men and Women by Use of the cobas TV/MG Test. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 59(10). https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.00264-21

Van Gerwen, O. T., Smith, S., & Muzny, C. A. (2022). Bacterial vaginosis in postmenopausal women. Current Infectious Disease Reports, 25(1), 7–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11908-022-00794-1

Vanderah, T. W. (2023). Katzung’s Basic and Clinical Pharmacology, 16th Edition. McGraw-Hill Education / Medical.

Woelber, L., Prieske, K., Mendling, W., Schmalfeldt, B., Tietz, H., & Jaeger, A. (2020). Vulvar Pruritus—Causes, Diagnosis and Therapeutic Approach. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2020.0126

Zheng, Z., Yin, J., Cheng, B., & Huang, W. (2021). Materials Selection for the Injection into Vaginal Wall for Treatment of Vaginal Atrophy. Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00266-020-02054-w

Sample of SOAP Notes Nursing #4

Subjective, Objective, Assessment, Plan (SOAP) Notes

| Student Name: LL | Course: | ||||||

| Patient Name: Hispanic or Latino | Date: 00-00-00 | Time: | |||||

| Ethnicity: Mexican | Age: 80 | Sex: Male | |||||

| SUBJECTIVE (must complete this section) | |||||||

| CC: “Had unprotected intercourse with an old classmate I recently learned passed because of HIV.” | |||||||

| HPI:

The patient is a 28-year-old Hispanic or Latino woman who expresses high anxiety and stress aroused from unprotected intercourse. About 4 months ago, the patient had sexual intercourse with an old classmate, and since his death from complications due to HIV, she has been deeply disturbed. These feelings that came to her amidst the familiar atmosphere of the home were fear, regrets, and severe uncertainty about her health condition. The patient’s anxiety has risen to new heights over the last week, driven by the fear of having been exposed to HIV and the burden of carrying its consequences. Even though the patient presented no distinct symptoms that looked like acute HIV infection, such as fever, sore throat, rash, and swollen lymph nodes, she became more concerned about her health and went to see a doctor. Unable to deal with the high rate of uncertainty, the patient has relied on search engines for information related to HIV transmission, symptoms, and treatment alternatives. Still, she remains concerned about the many unknowns about her health status. Even though the patient hasn’t received any particular treatments for the anxiety, she feels the immediate need for medical help to enquire about HIV testing. This episode has made her emotionally insecure due to possible HIV exposure. |

|||||||

| Medications:

None. |

|||||||

| Allergies: No known food and drug allergies (NKFDA)

Medication Intolerances: None Past Medical History (PMH) There is no past history of previous chronic illnesses or significant traumas. Hospitalizations/Surgeries: Surgery: Tonsillectomy 2001 |

|||||||

| FAMILY HISTORY (must complete this section) | |||||||

| M (Mother):

Passed away at 43 years old from complications of pneumonia. MGM (Maternal Grandmother): Died at the age of 91 from complications of renal failure. MGF (Maternal Grandfather): She died at age 105 after having complications of multiple organ failure. Father is still alive at the age of 61, with a history of major depressive disorder and prostate cancer. PGM (Paternal Grandmother): She passed away at 97 years old due to cerebral malaria. PGF (Paternal Grandfather): He passed away at 101 due to lung cancer. |

|||||||

| Social History: The patient is single and lives alone. She does not have any children. • Does not smoke or use tobacco. No recreational drug use. No use of illicit drugs. No recent travel history.She adds that she has family, friends, and siblings as her support system.Tobacco Use: Non-smoker.Alcohol Use:Non-drinker. Illegal Substance: No use of illicit substances. No recreational drug use. Marital Status: Single Sexual Activity: Sexually active Gender Identity: · Female Sexual Orientation: Heterosexual Occupation: Teacher. Nutrition History: Optimal nutritional status. Family Support: She uses her family and siblings as a support system. LMP: 29/04/2024. She has a regular menstrual cycle. |

|||||||

| REVIEW OF SYSTEMS (must complete this section) | |||||||

| General: Denies fever, chills, fatigue, or weight loss. | Cardiovascular: Denies chest pain, palpitations, or swelling of extremities. | ||||||

| Skin: Denies rash, lesions, or changes in skin color. | Respiratory: Denies cough, shortness of breath, or wheezing. | ||||||

| Eyes: Denies visual changes, pain, or discharge. | Gastrointestinal: Denies nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, or abdominal pain. | ||||||

| Ears: Denies ear pain, discharge, or hearing loss. | Genitourinary/Gynecological: Denies having dysuria or hematuria. Denies having a history of urinary infection. + Unprotected intercourse. | ||||||

| Nose/Mouth/Throat: Denies nasal congestion, sore throat, or difficulty swallowing. | Musculoskeletal: Denies joint pain, stiffness, or swelling. | ||||||

| Neurological: Denies headache, dizziness, or weakness. | Heme/Lymph/Endo: Denies bleeding, bruising, or lymphadenopathy. | ||||||

| Psychiatric: + Anxiety and fear regarding HIV exposure. | Breast: Denies breast pain. Denies abnormal nipple discharge. | ||||||

| OBJECTIVE (Document PERTINENT systems only, Minimum 3) | |||||||

| Weight:

65 kg |

Height: 165 cm |

BMI: 23.88 | BP: 121/83 mmHg | Temp: 98.6°F | Pulse: 76 beats per minute | Resp: 17 breaths per minute | |

| General Appearance: The patient appears well-nourished and healthy. Displays signs of anxiety. | |||||||

| Skin: The skin is warm and dry; no rashes or lesions are observed. | |||||||

| HEENT:

The head is normocephalic and atraumatic. There are no abnormalities observed. |

|||||||

| Cardiovascular: Regular rate and rhythm, no murmurs or gallops. The S1 and S2 sounds are heard. | |||||||

| Respiratory: Symmetrical expansion and relaxation of the chest wall. The lungs have clear sounds bilaterally. There is no wheezing or rales heard. | |||||||

| Gastrointestinal: The abdomen is flat and symmetrical in shape. Her abdomen is soft, non-tender, and non-distended. There is a bowel sound in all quadrants. | |||||||

| Genitourinary/ Gynaecology:

No lesions, discharge, or abnormalities were observed on the external genitals. |

|||||||

| Musculoskeletal: Complete range of motion on all limbs. There are no deformities or swelling on joints were detected during the examination. | |||||||

| Breast: No masses or abnormal discharge. | |||||||

| Neurological: The patient is alert and oriented to time, place, and person. There are no focal deficits were detected. The cranial nerves II-XII are intact. | |||||||

| Psychiatric: The patient is anxious and worried. The patient maintains eye contact and is fully cooperative during the examination. Rapport was established with ease since the start of the examination. | |||||||

| Lab Tests: An HIV test is to be done. | |||||||

| Special Tests: No orders have been placed at this time. | |||||||

| DIAGNOSIS (minimum required differential and presumptive dx, can do more) | |||||||

| Differential Diagnoses 1. Generalized Anxiety Disorder (ICD-10 code: F41.1):Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) manifests itself as persistent and excessive worry or anxiety in different spheres of life with no specific reason (Azab, 2022). In the context of this patient’s presentation, Generalized Anxiety Disorder could be considered because her significant anxiety and worry are related to exposure to the potentially deadly HIV. The patient’s manifestation of the symptoms of GAD includes high levels of anxiety, fear, and uncertainty. These coincide with the diagnostic criteria for GAD: inability to control worrying and excessive worrying. From a subjective point of view, the patient’s report of anxiety and horror after having unprotected sex with someone who is HIV-positive is a telltale sign of psychological distress (Carter et al., 2020). The HIV symptoms, which the patient does not have, make her generalize the anxiety. Subjectively, the patient’s vital signs might indicate a physiological state of anxiety, for example, by demonstrating an increased heart rate and blood pressure. Moreover, during the interview, remarks such as hypervigilance or nervousness on the part of the patient can also suggest GAD.2. Adjustment Disorder (ICD-10 code: (F43.2):Adjustment Disorder is defined by emotional or behavioral symptoms that respond to a stressful life event or significant life change (Karatzias et al., 2020). In this example, the physical symptoms of the patient after the recent HIV exposure may suggest that they are suffering from an adjustment disorder. The patient’s subjective report of increased anxiety and distress, which becomes most prominent in response to the perceived danger of HIV infection, is in line with the diagnostic criteria for adjustment disorder. Subjectively, the patient’s statement that she is overwhelmed and anxious after learning about her classmate’s HIV-positive status means she has an unhealthy response to the stressor. The patient’s concerns are about engaging in unprotected sexual intercourse with an individual positive for HIV (Mengwai et al., 2020). Subjectively, there might not be evident physical traits that prove adjustment disorder. However, these may be recognized in some forms, such as tearfulness, agitation, and constricting the body during this meeting. Furthermore, the patient’s recent life event serves as the perfect trigger for the onset of adjustment disorder. Treatment for adjustment disorder usually involves supportive therapy that helps the patient cope with the stressor and adapt to the new circumstances. Psychotherapy, for example, may involve supportive counseling or cognitive behavior therapy that will equip patients with the necessary strategies to buffer their emotions and improve coping skills. In some instances, medication use, such as antidepressants or anxiolytics, can be taken on a short-term basis to get rid of the symptoms of anxiety or depression.3. Hypochondriasis (ICD-10 code: (F45.2)A psychological condition known as hypochondriasis or illness anxiety disorder is marked by the presence of exaggerated concern and obsession with the idea of the existence of serious illness, even in the absence of physical indicators of medical illness (Arnáez et al., 2020). In line with the case, we may infer that the patient is potentially suffering from hypochondriasis as she has been worried and obsessed with the thought that she might acquire HIV even without any specific symptoms or signs. Subjectively, the patient’s complaints of heightened anxiety and distress, especially in the face of potential consequences of exposure to HIV, are in accordance with the diagnostic symptoms of hypochondriasis. The patient’s excessive worry and preoccupation with the perceived threat of HIV can cause her to interpret normal physiological sensations or minor symptoms as indicators of HIV infection (Siegel et al., 2021). Objectively, there would not be specific physical findings that have been found associated with hypochondriasis. Such behavior as excessive reassurance-seeking or the frequent use of medical services for symptoms that are thought to be severe might indicate a condition called hypochondriasis. Treatment of hypochondriasis often consists of CBT to correct the patient’s faulty beliefs and behaviors.

|

Presumptive Diagnosis (ICD 10 code)

Human Immunodeficiency Virus [HIV] Disease (ICD-10 code: B20) Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) disease is a chronic viral infection characterized by the progressive destruction of the immune system that results in the fatal condition Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) if not adequately treated (Patel et al., 2020). Such a hypothesis can be gained from the patient’s self-report of having acts of unprotected sex with an individual known to be HIV positive. This is a serious risk that, combined with the patient’s high anxiety and dread of acquiring an HIV infection, should prompt more diagnostic testing for HIV infection. Subjectively, the patient’s chief complaint of unprotected intercourse with a person whose infected status is unknown poses a threat of HIV transmission. This patient’s anxiety and anguish after the episode are similar to the mental response of many people who are afraid of HIV. The patient’s perception of the HIV disease severity, as expressed in her feelings about the classmate with HIV-related complications dying, reflects the grimness of the situation. The fact that there are not any particular characteristics of acute HIV infection present, such as fever, rash, or swollen lymph nodes, does not eliminate the possibility of an HIV disease (Liu et al., 2020). Nevertheless, the patient’s case history of having unprotected intercourse with an HIV-infected individual remains the leading risk factor for HIV acquisition. At this stage, though vital signs and physical examination findings may not reveal any HIV-specific abnormalities, baseline assessment and follow-up are crucial. Further diagnostic evaluations can confirm or rule out The proper definitive diagnosis. Such investigation may involve diagnostic laboratory testing such as serological tests (e.g., enzyme immunoassay, Western blot, or rapid HIV antibody test) to determine the presence of HIV antibodies or antigens in an individual’s blood. Besides, HIV RNA testing (viral load) is used to evaluate the amount of HIV in the bloodstream and determine the infection stage (Ulfhammer et al., 2021). Should an individual test positive for HIV, the immediate start of antiretroviral therapy (ART) is critical to stave off viral multiplication and preserve an individual’s immune system. The patient should also get overall medical management. This involves tracking for opportunistic infections, immunizations, and adherence support, which are essential for the patient’s health and quality of life. However, the presumptive diagnosis of HIV disease in this case emphasizes the indispensability of proper assessment, testing, and early intercession while dealing with HIV exposure. Collaborative efforts between health care providers and the patient are vital in overcoming the challenges of properly managing the health condition and the patient’s general health and well-being.

|

||||||

| Plan/Therapeutics:

Confirmatory Testing: Do HIV serology tests, including an enzyme immunoassay (EIA) and confirmatory Western blot, to firmly pinpoint the HIV infection. Run an HIV RNA test (viral load) to assess the amount of HIV in the bloodstream and define the stage of infection (Augusto et al., 2020). Evaluate immune function and disease progression by CD4 cell count testing. Immediate Initiation of Antiretroviral Therapy (ART): Start ART immediately when HIV diagnosis is confirmed to reduce viral load and protect immune function. The patient starts getting Antiretroviral Therapy (ART), which is a combined regimen consisting of Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) 300 mg and Emtricitabine (FTC) 200 mg (Truvada) plus Dolutegravir DTG 50 mg (Tivicay). Truvada, a fixed-dose combination pill, will be administered daily orally to the patient with the required TDF and FTC doses (Vanderah, 2023). In addition, Tivicay, an integrase strand transfer inhibitor, will be ingested orally once daily. These drugs block different stages of the HIV replication cycle; their combination provides the synergism for suppressing viral replication and preserving immune functions. Individualize ART regimen for viral load, CD4 count, comorbidities, and drug interactions (Michienzi et al., 2021). Emphasize the role of compliance with ART in reaching and maintaining viral suppression, lowering the probability of drug resistance, and maximizing treatment results. Monitoring and Follow-up: Arrange for routine check-up sessions to closely examine the drug responses, ensure proper adherence, and check for medication side effects or complications (Abera et al., 2023). Conduct lab tests frequently, including HIV viral load, CD4 count, complete blood count, renal function, and liver function tests, to track disease course and treatment effect. Offer ongoing education and assistance to handle any issues related to HIV management, including medication adherence and lifestyle modifications. Preventative Measures: Give pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to individuals with high risk, including sexual partners, to reduce HIV transmission (Huang et al., 2020). Advocate for consistent and accurate condom use as a way to reduce HIV transmission during sexual activities. Discuss harm reduction programs that offer tools like needle exchange where HIV infection through injection drug use is a threat to these groups of people. Psychosocial Support and Counseling: Lend comprehensive psychosocial support, including counseling, mental health services, and peer support groups, to mitigate the emotional and psychological effects of HIV diagnosis and treatment (Okonji et al., 2020). Refer students toward other services for extra guidance through social workers, housing assistance, and financial schemes. Routine Healthcare Maintenance: Provide routine preventive care, including vaccination, cervical cancer screening (Pap smear), and sexually transmitted infections (STI) screening to keep overall health and well-being in good condition (Strickler et al., 2020). Carefully observe for and immediately take care of any HIV-related complications or comorbidities, which are infections, cardiovascular disease, and metabolic disorders (Fantasia et al., 2020). Partner Notification and Testing: Promote partner notification and testing of the identified partners and provide them with the link to HIV treatment and prevention services. Offer advice on how to tell about HIV status to sexual partners and possible contacts and provide communication techniques.

|

|||||||

| Diagnostics: